How the convergence of Government policy, timber innovation, and modular construction offers a lifeline to public estates facing the dual crisis of capacity and climate.

The UK public sector estate is currently navigating a perfect storm. On one hand, there is the undeniable urgency of capacity: schools are grappling with rising SEND demands and crumbling RAAC-affected infrastructure, while the NHS faces a perennial need for rapid expansion. On the other, there is the existential stricture of the Climate Change Act: the legal requirement to decarbonise.

For years, “sustainability” in public procurement was often a “nice-to-have” value engineering casualty. Today, it is a necessity of design. With the Public Sector Decarbonisation Scheme (PSDS) Phase 4 now allocating critical funding through to 2028, and the Department for Education’s GenZero standards setting a new bar, the question for Heads of Estates is no longer if they should build sustainably, but how they can do so affordably and rapidly.

The answer, increasingly, lies in a synergy of three distinct elements: a shift in carbon definition, the Government’s endorsement of timber, and the maturation of Modern Methods of Construction (MMC).

The Two Faces of Carbon: Operational vs. Embodied

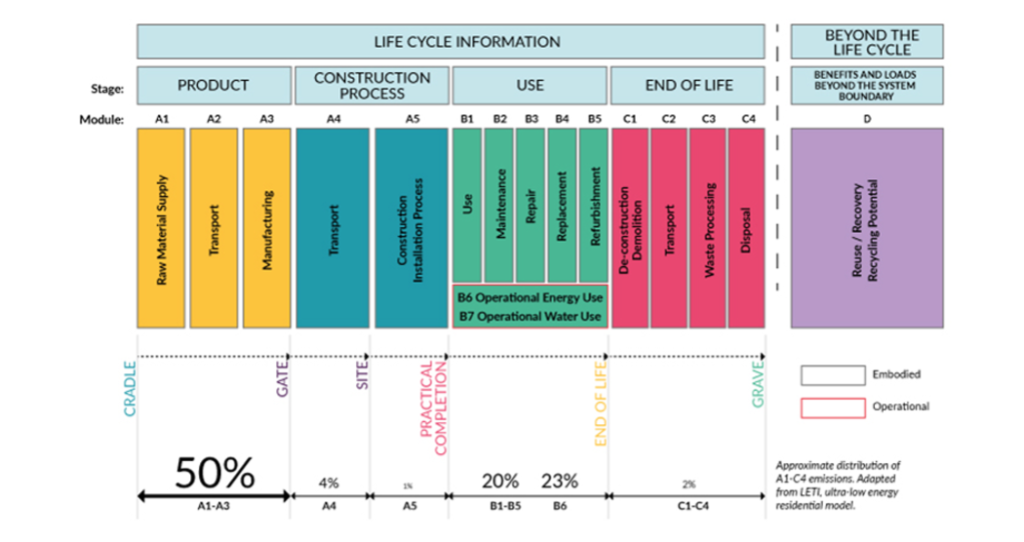

To understand the solution, we must first redefine the problem. For the last decade, the construction industry’s focus has been heavily skewed toward Operational Carbon: the emissions generated by heating, cooling, and powering a building. We have become very good at reducing this. Through the widespread adoption of LED lighting, solar PV, and heat pumps, coupled with the rapid decarbonisation of the National Grid, operational emissions are falling.

However, as Operational Carbon decreases, Embodied Carbon—the emissions released during the extraction, manufacturing, transport, and construction of building materials—rises in relative importance. According to the UK Green Building Council (UKGBC), Embodied Carbon already accounts for nearly 20% of the UK built environment’s emissions. By 2050, it is projected to make up over half of the carbon footprint of new construction.

This presents a challenge for traditional construction. Concrete and steel are carbon-intensive heavyweights. To hit true Net Zero, the public sector cannot simply add solar panels to a concrete block; it must fundamentally change the fabric of what it builds.

The “Timber Revolution” and Government Policy

Recognising this impasse, the UK Government published its Timber in Construction Roadmap, a policy paper that effectively gives the green light to a material renaissance. The Roadmap acknowledges a stark reality: using timber can reduce the embodied carbon in a single building by anything from 20% to 60%.

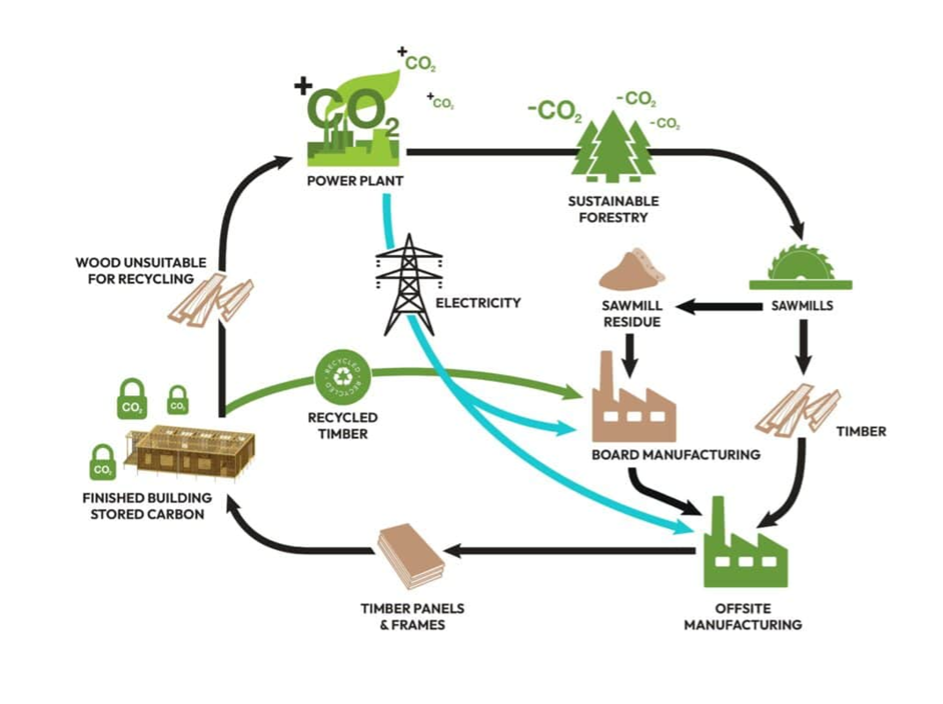

TG Escapes, a leading provider of modular eco-buildings to the education and public sectors, has analysed this roadmap extensively. Their experts note that while steel and concrete have their place, they do not act as carbon sinks. Timber is unique. As trees grow, they sequester carbon dioxide; when harvested and used in construction, that carbon is “locked in” for the lifespan of the building.

As noted in TG Escapes’ analysis of the roadmap: “Timber is one of the only truly sustainable products in construction… Every dry tonne of wood used in construction preserves 1.8 tonnes of CO2, a stark contrast to the 1.4 tonnes of CO2 emitted per tonne of steel produced.”

The Timber Lifecycle

The Roadmap is not just about environmentalism; it is about economics and supply chain resilience. It sets out to increase the sustainable supply of timber, address fire safety through the new Mass Timber Insurance Playbook, and promote innovation in high-performing timber systems. For public sector specifiers, this is a clear signal: the Government wants to see wood in public buildings.

Modular: The Delivery Mechanism

If timber is the material solution, modular construction is the methodology that makes it viable for the public sector.

The traditional critique of eco-buildings is that they are slow or expensive to build. Modular timber construction flips this narrative. By manufacturing buildings off-site in controlled factory environments, providers like TG Escapes can deliver projects up to 30% faster than traditional builds. This speed is critical for public bodies operating on strict fiscal timelines, such as those governed by PSDS funding windows where failure to deliver can result in clawback.

Furthermore, the factory environment significantly reduces waste. Traditional construction sites are notorious for material wastage, whereas off-site manufacture can reduce waste by up to 90%. TG Escapes’ research highlights that off-site manufacturing reduces carbon output by up to 45% compared to traditional methods, driven by fewer deliveries and precise adherence to specifications.

What Does “Net Zero” Actually Look Like?

For a public sector client commissioning a new school block or healthcare facility, “Net Zero” can feel like a nebulous term. It is helpful to break it down into two practical classifications, as defined by industry leaders:

1. Net Zero in Operation: This is the standard baseline. It requires a “fabric-first” approach. Instead of relying on expensive technology to heat a leaky building, the building envelope itself is engineered to be airtight and highly insulated.

- Technology: It incorporates Mechanical Ventilation with Heat Recovery (MVHR) to maintain air quality without heat loss, smart LED lighting, and renewable generation via rooftop solar panels and air source heat pumps.

- Result: The building generates as much energy as it consumes annually.

2. Net Zero in Lifetime: This is the gold standard. It accounts for the building’s entire existence, from the “cradle” (material extraction) to the “grave” (demolition).

- Strategy: This requires low-carbon materials (timber) to minimise upfront emissions, but also plans for the end-of-life. Unlike concrete, which requires energy-intensive crushing, a modular timber building can be dismantled, and its components reused, recycled, or used as biomass fuel.

- Result: When combined with sustainable forestry (FSC/PEFC certified), the building can effectively be carbon neutral or even carbon negative without heavy reliance on offsetting schemes.

Timber vs Traditional Construction: A Carbon Model.

Comparing the carbon footprint of an average sized building constructed using a timber frame modular system against traditional construction methods, we see a 22% reduction in carbon of across the lifetime of the building, but before end of life disposal.

However, this excludes sequestered carbon within the timber which can be reclaimed or recycled as per the timber lifecycle model. Industry data analysed by The Construction Index shows that including this can reduce the embodied carbon in construction and end of life by up to 90%.

The “Invest to Save” Opportunity

The perception that sustainable building is a “premium” product is outdated. In the context of the public sector, it is an “Invest to Save” mechanism.

Firstly, the energy efficiency of a Net Zero modular building drastically reduces running costs—a vital factor for schools and local authorities where energy bills have decimated discretionary budgets. A building that generates its own electricity offers immediate revenue relief.

Secondly, the “biophilic” nature of timber buildings—using natural materials and light to connect occupants with nature—has proven benefits for occupant wellbeing. In educational settings, this translates to better focus and behaviour; in healthcare, it creates calming and healing environments. This “social value” is increasingly a metric in public procurement (PPN 06/20).

Conclusion: A Mandate for Change

The path to 2050 is not paved with concrete. The convergence of the Government’s Timber in Construction Roadmap and the maturity of the modular sector provides a clear template for the future of public buildings.

For the public sector, the risk lies not in innovation, but in inertia. Continuing to build with high-carbon, slow-to-deploy traditional methods is a financial and environmental liability. By embracing timber and MMC, the public sector can deliver the capacity it needs today, while securing the environment we need for tomorrow.

As the industry moves toward strict carbon limits, the question for every new project must be: Why not timber?